What is a deck? Is it the sum of its parts, or is it somehow greater? Perhaps, in some cases, could it be lesser? We all understand the value of cards within the context of a game of Magic, but let us examine what those cards say in another context.

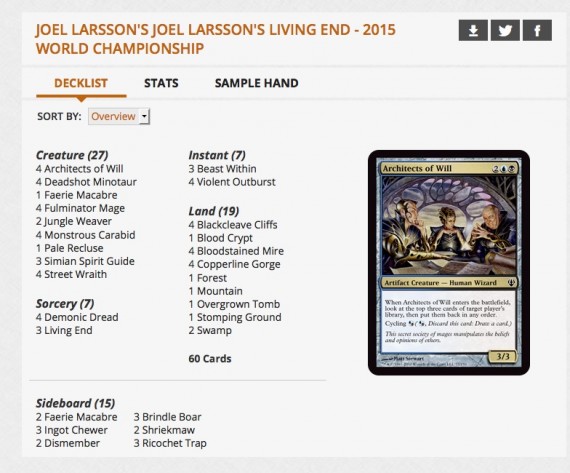

4 [card]Architects of Will[/card]

These creatures believe themselves to be shaping their own future, but in truth, time is an illusion and the exercise of the will futile. As we will see as we delve deeper into this deck, the ultimate fate of all life is death and the only architecture we can shape is the brutalist angles of our own misery.

4 [card]Deadshot Minotaur[/card]

The minotaur mythos comes to us from ancient Greece, where the singular beast, an aberrant offspring created by a blasphemous union, dwelt forever alone at the center of a complex maze and devoured the companions given to it. It was eventually slain by a self-styled hero. Now we see a troupe of minotaurs, no longer singular but a quartet, forever seeking vengeance. However, they are confounded time and again, for as they target a flying hero, they find that once again that hero has flown too close to the sun, and rather than the minotaurs being the instrument of death, they are reduced forever to nothing but witnesses of it, helpless in the face of another catastrophe, ad infinitum.

1 [card]Faerie Macabre[/card]

This faerie is macabre, yes, but can we blame it? The faeries of Lorwyn are forever cursed to watch as over and over again their idyllic dreamscape is reduced to a dark reflection of itself. This is a curse, but is also a gift, the gift of clarity. For in fact the dark reflection is the true world, and the only rational response to the cruel oblivion of reality is unrelenting nihilism. This faerie understands this, for it has cast off its family to inhabit the decklist alone, a singleton in the first game of each match.

4 [card]Fulminator Mage[/card]

The fulminator mage is a cautionary tale against primitivism. They tell a story of a desire to return to a simpler time, but in truth it is a fiction. They desire only to see the trappings of the modern world burned to ash and smashed to rubble, they dream of a graveyard that will spread to contain all lands.

2 [card]Jungle Weaver[/card]

The jungle weaver has both cycling and reach. In reach we see a desire to touch the sky, to feel the flutter of wings. But the destiny of the jungle weaver is instead cycling, to be sent to the house of the dead before it has even lived. This is the fate of all who reach for their desires, for the world is cruel and cannot abide success.

4 [card]Monstrous Carabid[/card]

What is it about the carabid that renders it monstrous? It must attack, yes, but is that truly monstrous? I say it is a virtue. For all creatures have a purpose, but only the carabid is driven to fulfill it. The carabid has reduced existence to a simple binary. It will kill the enemy, or it will die. Perhaps it is not unusual for those with a grim clarity of purpose to be called monsters, but if the carabid is monstrous for removing our choice to attack, are we not then a thousand times more monstrous when we send creatures to battle that could have followed a path of peace?

1 [card]Pale Recluse[/card]

The recluse, too, has admitted defeat in the fight against its own nature. It does not seek companionship, but instead resides in the deck alone. Like the jungle weaver, it reaches for lofty goals, but also like the jungle weaver, all too often its dreams are thrown into the refuse heap of reality. Sent to lie in a shallow grave until it can be called upon, the recluse rarely blocks but is instead sent to do battle time and again, until it barely remembers its tower home.

3 [card]Simian Spirit Guide[/card]

While the other creatures in this deck have long grown weary of the mortuary stillness they often inhabit, the spirit guide yearns for it. Only he knows what it is to be denied death and life simultaneously, to exist outside of time for a brief eternity. We must consider, is life a gift we are given, or is it but the wrapping paper we must peel from the true gift, death?

4 [card]Street Wraith[/card]

What is life? What is death? For the street wraith, one is a coin, the other a destination. The street is metaphorical, a highway to the grave, paved with unmet expectations. The street wraith promises nothing, but leaves something in its wake nonetheless. What does it leave? Different each time. Only you can know if you have been given a reward or a punishment.

4 [card]Demonic Dread[/card]

What is the dread here? Is it dread of demons, or is it instead the dread that there are no demons, no evil, and thus no good? That our decisions are our own, that we bear the full burden of their responsibility. That there is no God, no Heaven, No Satan, No Hell, only a brief unfulfilling life and then oblivion?

3 [card]Living End[/card]

Is this the end, or the beginning? Life and death are forever entwined here, but in truth they have always been entwined, everywhere. They are two sides of the same coin, and we have no choice but to flip it, over and over, until the wrong side comes up and we pass into the dying light.

4 [card]Violent Outburst[/card]

We can react to the knowledge of our own demise with violence, with stoicism, with fear or longing. But in the end, our reactions, as our lives, will be forgotten. None will mourn our passing for more than a brief span, just as we mourn those we remember only until it is time to forget.

3 [card]Beast Within[/card]

Beast Within is a good answer to graveyard disruption such as [card]Leyline of the Void[/card], but it is also strong against Tron and Splinter Twin. You can use it to break up the third Tron piece, destroy a Karn, or blow up a Deceiver Exarch in response to a Splinter Twin or Kiki-Jiki.